I stick, therefore I am.

At a coffee shop in Berlin, three Minerva students are working on their assignments.

A person comes in: Person: “Sprichst du Deutch?”

Minervan:“Hmm, nein, Es tut mir Leid.”

Person: “English?”

Minervan: “Yes.”

Person: “Ah, would you allow me to play in this piano for some minutes? I promise it won’t take long.”

Minervan: “I’m sorry, but I don’t have cash.”

Person: “No, no, I just want to play. Would that disturb you?”

Minervan: “Go ahead.”

Today capitalism affects everyone’s lives in the form of exciting individualism and

private properties. Time, space, and resources have become more valuable than money itself. The

musician who just wanted to play did not want any money. The coffee shop becomes a patron

because it hosts a working piano, but the Minerva students too are patrons. They agreed to share

space-time, which allowed the artist to practice his music.

The heart of Berlin beats on the street

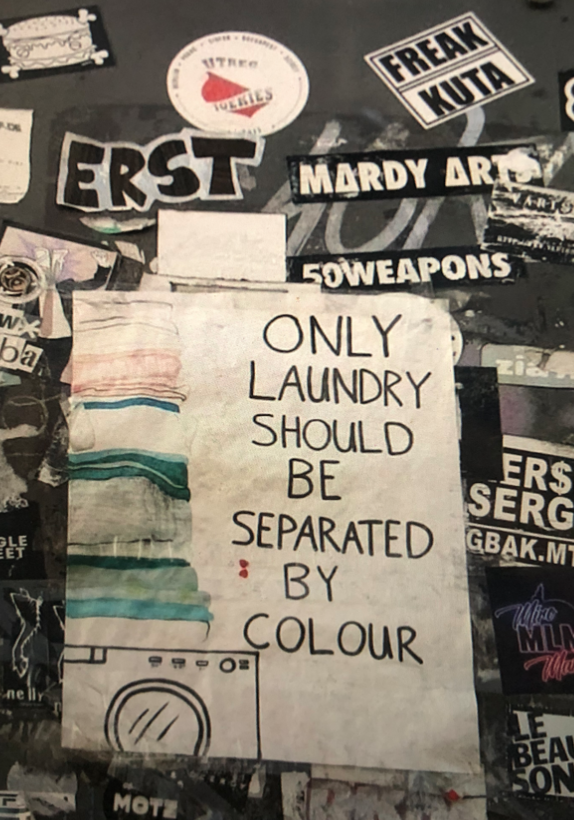

Graffiti artists value effectiveness and quickness since they have to avoid law and

conservative passersby problems. Freehand spraying requires a lot of time, and stencils are quite

limiting creative-wise. Stickers are less time-consuming to be put on the street than graffiti and

are not permanent. Even if you use the best glue, they will start to decompose at some point or

get removed. You can make as many stickers as you want, and they’re not dependent on the artist

to be distributed on the street. Being very easy to circulate just anywhere, stickers are used as a

form of communication, expression, protest, and interaction.

The relationship of the patron to the art, and space

Since works of art commissioned by wealthy patrons usually reflect their desires and

aims, a democratized patronage makes it possible for artists to claim their voices. Today, the

patron-artist relationship is no longer based on just monetary support. A curator (as a patron) is

an urgently necessary role within an art world that is becoming dominated by capitalism

(Cheng).

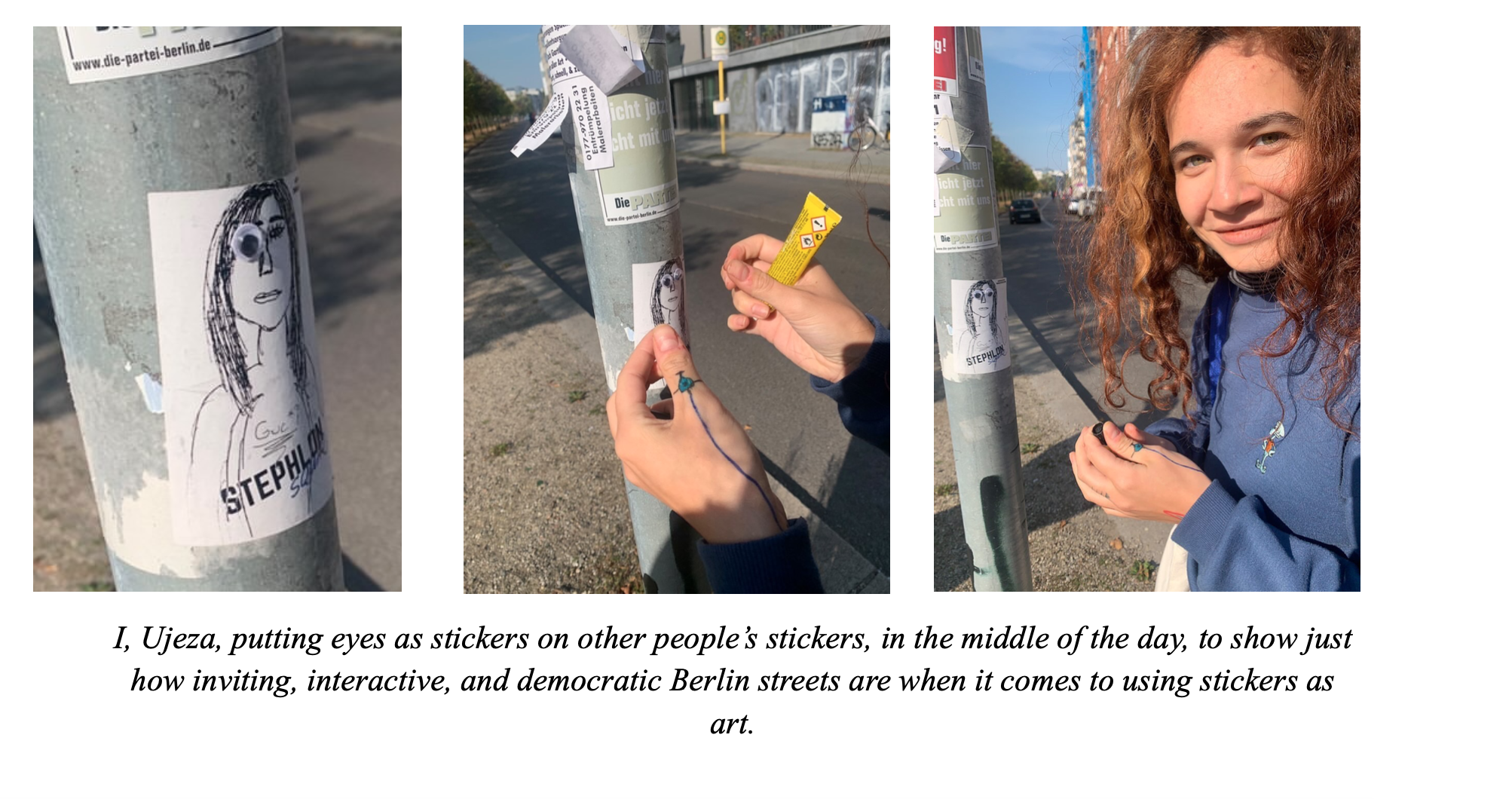

Patronage can also take the form of preservation or protection, or the artist contributes as a

patron. By continuously putting stickers in the street, the sticker culture is maintained. The same

artists decide where to stick their stickers and hide other stickers with theirs. Since you don’t

have to be an artist to put a sticker on the street, just anyone can do it. A patron can be the

distributor of the sticker, and they can be an ordinary Berliner. Primarily we define what is

considered “art” to determine its patron. For example, the artist is the designer, and the person

putting the sticker up for the artist is the patron. We have sticker artists like sticker maid berlin

that use stickers to react to other stickers, posters, advertisements, graffiti - thus creating

interactive art (Sticker maid Berlin, 2019). The patron here can be the other artist who put the

sticker up to which the artist is using her sticker to react. If the initial sticker did not exist, the

artist would not make her sticker reaction art.

The impact of this patronage on the cultural life of the city

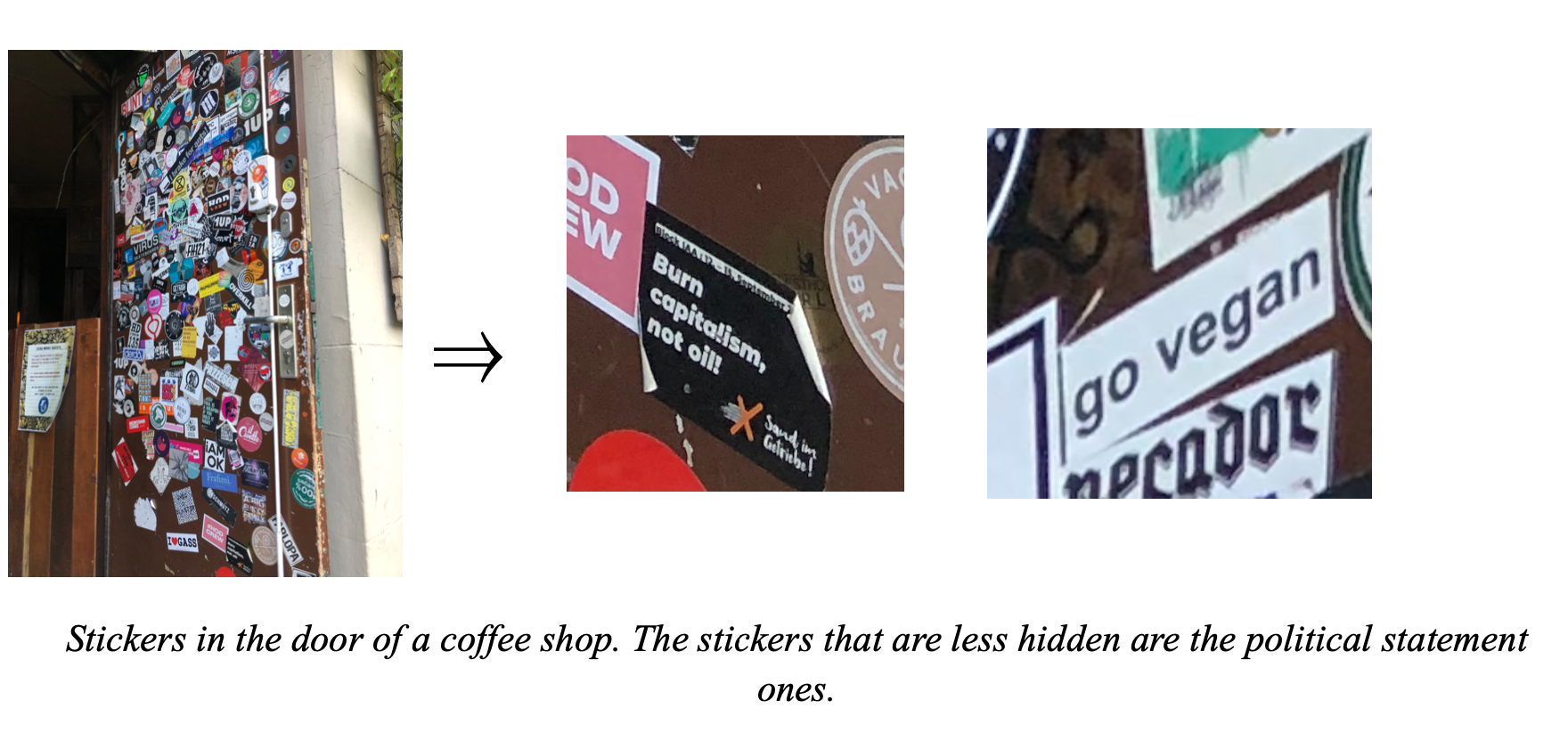

The majority of stickers show what voices are mainly supported. Usually, If you’re not a

worldwide famous street artist, your work gets replaced by someone else’s. In Berlin, this

depends on the art itself since most of the sticker artists are anonymous. Stickers that are not

hidden by other stickers/posters mean they are valued. Berliners make consequential claims

against gentrification and capitalism through the political stickers street performance in Berlin.

They draw attention to questions surrounding the relationship between public space and private

property, dating since the Berlin wall fell in 1989. Even if there is not a physical wall dividing

East and West Berlin, economic, social, and cultural norms are still apparent on both sides.

Stickers are used to patch up those divisions

.

Berlin as a city supports the sticker culture by creating institutions dedicated to stickers.

The first and only sticker museum is located in Berlin (Hatch Sticker Museum). Irmela

Mensah-Schramm, a retired teacher, goes around Berlin and scrapes off stickers with hate and

extremist speech. She was given numerous humanitarian awards, including the Göttingen Peace

Prize, Silvio Meier Award, and Order of Merit from the Federal Republic of Germany. In 2016

Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin hosted an exhibit named “Sticky Messages:

Anti-Semitic and Racist Stickers from 1880 to the present (Schweppe, 2021). Recently a movie

was released named “Notes of Berlin,” based on a blog created for Berliners to post stickers and

notes they find on the street. The movie is set out to educate citizens about the significant role that stickers play in everyday life (Köhnemann, 2021).

Contrariwise, in Seoul, you find typical articles with titles such as “Graffiti can harm historical heritage” and “Graffiti causes inconvenience for shopping district and citizens”(Kim, 2019). Ihwa Village is well known for its murals created as a project from the state to attract tourists. As domestic and foreign tourists come to see the murals, residents complain of the noise from the tourists and the wastes they make (Lee, 2016). Here, residents protested against the state decisions by covering the murals with grey paint, whereas Berliners flood the streets with stickers to reclaim their space. Maybe when, and if, South and North Korea break their “wall”, the citizens will use stickers to patch their differences created by the 70 years of seperation too.

notes they find on the street. The movie is set out to educate citizens about the significant role that stickers play in everyday life (Köhnemann, 2021).

Contrariwise, in Seoul, you find typical articles with titles such as “Graffiti can harm historical heritage” and “Graffiti causes inconvenience for shopping district and citizens”(Kim, 2019). Ihwa Village is well known for its murals created as a project from the state to attract tourists. As domestic and foreign tourists come to see the murals, residents complain of the noise from the tourists and the wastes they make (Lee, 2016). Here, residents protested against the state decisions by covering the murals with grey paint, whereas Berliners flood the streets with stickers to reclaim their space. Maybe when, and if, South and North Korea break their “wall”, the citizens will use stickers to patch their differences created by the 70 years of seperation too.

Resources:

08. Stickermaidberlin - STICKEM - Sticker culture project. Stickem. (2019). Retrieved October 8, 2021, from http://stickemzine.com/en/stickem-2019/stickermaidberlin/.

Cheng, A. (n.d.). Expanding the vision for Arts patronage. ArtAsiaPacific. Retrieved October 8, 2021, from http://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/102/ExpandingTheVisionForArtsPatronage.

Hatch Sticker Museum. Urban Nation. (2021, February 25). Retrieved October 8, 2021, from https://urban-nation.com/artist/hatch-sticker-museum/.

Kim, J.-min. (2019). Is graffiti art or vandalism? The Dongguk Post. Retrieved October 8, 2021, from https://www.dgupost.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=2602.

Köhnemann, A. (2021, September 9). Notes of Berlin (2020). Startseite. Retrieved October 8, 2021, from https://www.kino-zeit.de/film-kritiken-trailer-streaming/notes-of-berlin-2020.

Lee, K.-min. (2016, May 13). Ihwa residents want to remove murals. koreatimes. Retrieved October 8, 2021, from https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2021/06/113_204705.html.

Schweppe Peter Schweppe is Assistant Professor of German and History at Montana State University. Over the years he has lived in Toronto, P. (2021). Sticking to it: Barbara. and Irmela Mensah-Schramm. @GI_weltweit. Retrieved October 8, 2021, from https://www.goethe.de/ins/us/en/kul/art/abi/21442692.html.